Hi friends,

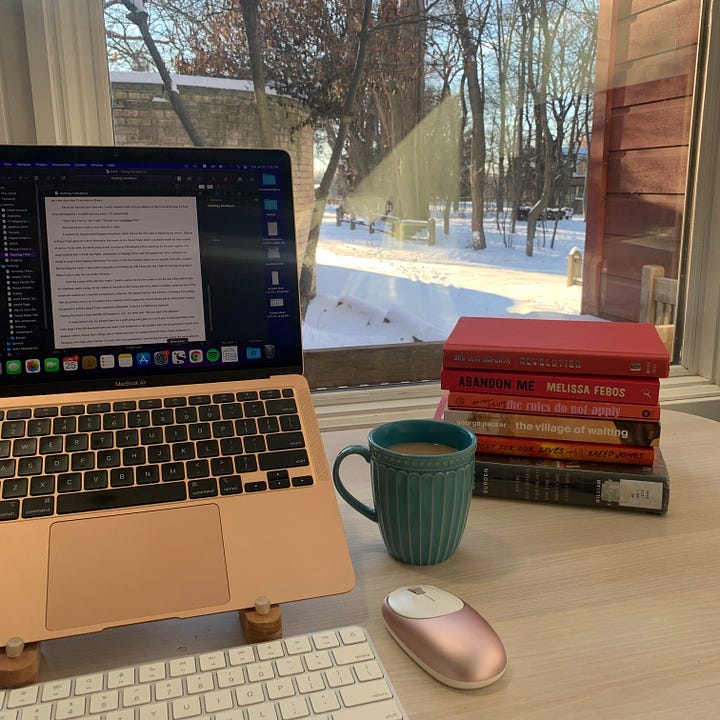

I want to tell you the story of my memoir. I call it a secret story because I don’t often talk about it, especially not with people I know. Outside of classmates from various writing workshops over the years, very few people have read my draft. Not even my husband has seen more than a handful of pages.

“How’s your book going?” a friend will inevitably ask. “Slowly,” I always respond, which is true but also glosses over everything else — how aimless I feel most times, how I know my story is important to tell but I haven’t totally figured out why, how many times I’ve gone steadfastly in a specific direction only to find myself wandering in circles. Writing a book, I’ve come to find, means perpetual wandering, and I don’t know how to explain that to those who’ve never undertaken it themselves.

Still, I want to share the story of how I got here because reading reflections like this would’ve been helpful when I started my project eight years ago1. Because creative works have a life of their own before they enter the world of public consumption. And because it’s a reminder to me that although I’m far from finished, I’ve already done a lot of work, and that work is worthwhile.

So, here’s the story of my memoir (so far).

In June 2011, I stuffed my life into two, bulging suitcases and moved to Ecuador to begin my service as a Peace Corps volunteer. Coincidentally, I’d been to Ecuador before. In college, I’d spent six weeks studying Spanish in Cuenca. I’d fallen in love with Cuenca’s blue-domed cathedral, the charming Spanish-style balconies, and the Andes mountains. I dreamed of returning again someday.

I knew it wasn’t likely, but I signed up for Peace Corps with the whispering hope that they’d send me back2. My recruiter told me I’d likely go to Eastern Europe, where there was a large need for English teachers (the only thing I was qualified to do). Then, miraculously, they opened the first English teaching program in Ecuador and before I knew it, I was flying back to the Andes mountains again, just as I’d dreamed.

In Peace Corps, I taught English as a second language in high schools and universities. I learned to speak Spanish for real. I made friends and traveled and fell in love. I shattered my life to pursue a dream and it broke me open, reshaped who I am as a person. Then I shattered my life again when I finished my service, said goodbye to everyone I knew in Ecuador, and moved back home.

Three years later, I began writing a memoir about that experience. By now, I was living in Chicago and working a regimented corporate job. My time in Ecuador seemed like a fever dream, closer to fiction than reality. At the encouragement of writing mentors and friends, I began writing about it. I didn’t know what I wanted to say, but I wanted to understand what my service meant. After all this time, I’d only just begun to relocate my sense of direction. I wanted to understand who I was when I landed in Ecuador that summer years ago and who I was now as I tried to determine where my life would go next.

Of course, there were a lot of things I didn’t know as I set out on this venture.

I didn’t know what it meant to be a writer. According to my graduate classes, you had to write every day, and according to the famous writers, you had to write first thing in the morning. It was better to have an MFA, but I didn’t have the time or money for that, so I resolved to do without.

I didn’t know what made a memoir. I’d been writing fiction until my final year of graduate school when I discovered there was a name and a genre for telling true stories: creative nonfiction. I took a class and wrote some personal essays, but I definitely didn’t feel like I understood the genre.

I also didn’t know how to write a book. How did I organize so many story lines? How did I render real people on the page? Where did I even start?

Most of all, I didn’t know how freaking long it would take.

As I set out on this journey, I struggled to be what I thought a writer was. I didn’t write every day. A night owl by nature, I snoozed through my morning writing sessions and felt like a failure. To really be a writer, I thought I had to quit my job and devote myself to my projects. The problem was that I didn’t know how to make money outside of a traditional nine to five, and working a service job wouldn’t pay my bills. Instead, I decided I’d spend a year building a dedicated writing practice. If I could be serious, I told myself, then I could quit my job. So, I got serious.

In 2018, I took a Memoir in a Year class at StoryStudio with 10 other working professionals looking to write their books into reality. By the end, we joked that it should be called Memoir for a Year because none of us finished our drafts. I know now how naive it was to think I’d finish my book in a year3, but the class jump started my drafting process. It also forced me to wrestle with the main questions of a book. What would the structure be? What themes were coming up in my writing, and how did I want to explore those over the course of the book? What was important to tell and what wasn’t?

After finishing the year, I craved the support and structure I’d had in class. Despite getting serious about my book, I knew that quitting my job to write “for real” wasn’t feasible. Now, I also knew that writing full-time wasn’t the only way to be a “real” writer. From 2019-2021, I periodically worked with manuscript coaches, whose feedback helped me maintain my momentum and begin honing my story arc. Through our sessions together, I realized that the memoir-in-essay structure I’d pursued was not conducive to the deeper exploration my themes demanded. I resolved to change my structure, and I called my first draft done, even though I’d yet to write large swaths of my story.

(In retrospect, I probably should’ve focused on writing the story from beginning to end before I brought in outside voices. But I didn’t know what I was doing! As it turns out, there’s not one tried and true way to write a book, despite my endless quest to find it.)

In 2022, a personal dream came true: I got accepted to a residency! The Omicron variant swept across the country that winter. I was terrified of getting sick, but even more terrified of missing my chance to devote myself to my own artistic projects. For three weeks, I worked alongside fiction writers, playwrights, dancers, and musicians. After spending two years in near total isolation, those three weeks of talking about creativity by a roaring fire healed my soul. One night, I listened to a brilliant cellist from the Minnesota Orchestra talk about feeling like an imposter and realized that the feeling never goes away, no matter the level of your talent or commitment. I wrote four chapters of my book and realized that I am a writer, just as serious as anyone else.

In 2023, I began a year-long memoir generator course with a well respected online magazine that offered writing classes with published authors. I couldn’t believe I’d been accepted, and I hoped this would provide the structure and accountability I needed to complete the second draft of my memoir in its new structure. The class was challenging. My fellow students were brilliant, and I often felt like I could barely keep up with their keen observations, their evocative and emotional writing. Then, a curious thing started happening: after many classes, especially those where we’d workshopped my pages, I ended up in tears. I’d been in creative writing classes for over ten years and workshopped hundreds of pages. I knew how to hear critique without crying. But suddenly, I couldn’t stop crumpling into tears.

“Are the students being assholes to you?” a friend asked gently. We’d both been in workshops where cruelty masqueraded as constructiveness. But my classmates weren’t being assholes. In fact, they’d been nothing but kind, empathetic, and helpful.

Five months into what should’ve been a year-long class, the organization imploded and our teacher unceremoniously announced that we’d no longer be meeting. We begged her to continue. We proposed creative ways we could band together to get through the year, despite the organization’s demise. We’d spent months building tender emotional connections to each other and our work; we didn’t want to just give up. When she refused to give us a morsel of further guidance, I realized it had been the teacher all along. Through a hundred tiny remarks and gestures, she’d made me feel like I was emotionally deficient, like my story was worthless, like I wasn’t creative enough to write a memoir. Later discussions with my classmates revealed that she’d made them feel the same way. In a million little ways, she’d slowly shaved down our confidence until we all doubted our voices.

For the first time since I’d begun my project, I took a substantial break. I needed some time off from feeling bad about my work.

Then I had a baby. During those early months, I worked over naptimes even though I could barely keep track of what I’d done from one session to another. Then I began avoiding my book altogether. After nearly nine months away from the manuscript and eight years of total work, I felt like I should be so much closer to being done. Yet, I have so far to go.

And that brings us to today. This book and I have been on a long journey together, and I refuse to let it end here. I don’t wonder so much anymore about who I am and how those two different versions of myself fit together. I’ve been many different versions of myself since then. But I do wonder about what it means to help others, to live by our values and move towards the person you want to be. I look back at twenty-something me and have so much compassion for what she navigated on her own, for the bravery it took to uproot her life and follow a dream. I think that her story is miraculous, a good story in the classic sense of the word, a story worth telling. It was a story that shaped me, even if I no longer need to know exactly how (though I have a feeling I’m going to find out in the course of writing this, anyways!).

When it comes to not writing, Alexander Chee says you have to forgive yourself for your time away from the page and simply start again. It’s easier to keep avoiding my book, to tell myself I’ll get to it when my son’s older while I quietly worry that my Peace Corps memories are getting sucked into the black hole that is my postpartum brain. But my heart knows it’s time to start again. Will I eventually find my way on this winding path? Only time will tell.

Let’s keep chatting

Speaking of pulling back the curtain on the book writing process, I love the Memoir Land Author Questionnaire from Sari Botton. This one with Laurie Woolever resulted in a lot of exciting additions to my TBR.

What creative projects are you working on these days? What do you do to break out of a creative rut?

Lord help me.

At that time, applicants had very little say in where they were placed. Instead, they were sent to the country with the most need for their skill set. The Peace Corps has since updated their application process to allow volunteers to apply by location and program, similar to a traditional job search.

Though some folks do!

Thanks for sharing your experience, I've been working on a novel and big head nods to "Most of all, I didn’t know how freaking long it would take." I appreciate your advice around waiting to bring in outside voices. Your story sounds beautiful, I'm wishing you times with the pages and cheering you on!

I would love to read a memoir about working for the peace corp and teaching English and living in Ecuador! Keep writing.

My novel has taken me a long time too. Life sent me a bunch of major hurdles, and I made my own mental ones as well. I've sent my book out to around ten agents and then just stopped. I think about abandoning it altogether, but then I think about all that I have put into it. Time and money and heart.

Let's not give up. Your essay inspired me to keep going. Thank you.